Article by: Nelmynce

Beholder‘s an interesting little game that keeps asking you one question– Where do your loyalties lie?

Graphics

The first thing that hit me about Beholder is that the screenshots don’t do it justice. The intro sequence starts with a simple 2D view of the letter you’ve received letting you know that you’re the newly appointed landlord, and then suddenly swoops into a 3D introductory sequence of you (Carl Stein) and your family on the bus to your new home.

The intro is restricted to a black and white palette, but the direction of it is fantastic, and communicates in a very short period of time everything you need to know before you get to the apartment.

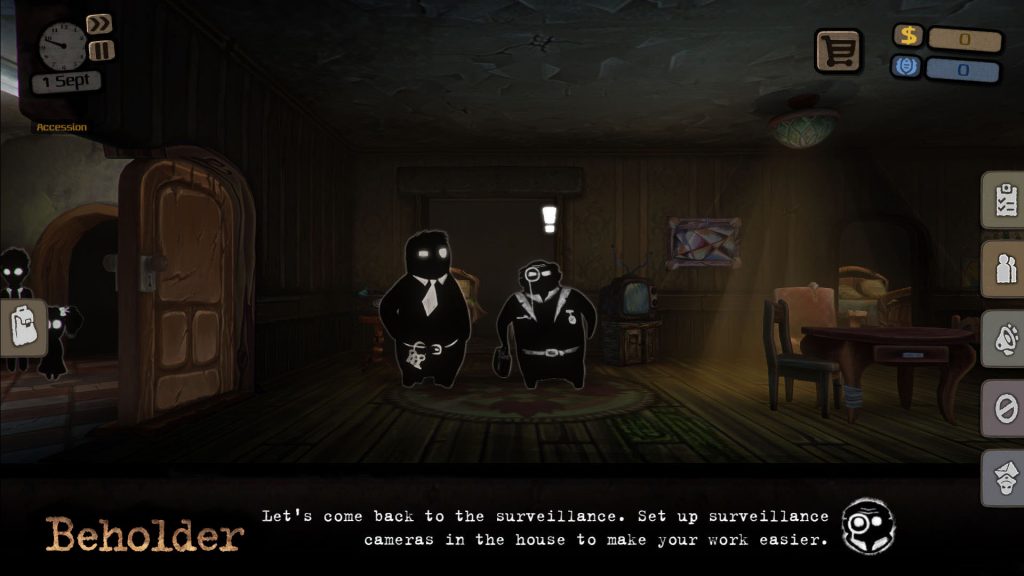

Once you’re in the apartment, the game takes on an interesting blend of 2D and 3D. The building itself and all the objects in it are fully rendered in three dimensions and are fully colored, but the characters themselves take on a two-dimensional look and retain the stark monochrome aesthetic of the intro, which makes them very easy to track against the more colorful background of the apartment– and tracking people is something you’re going to be doing a lot of.

Story

You play as Carl Stein, a newly state installed Landlord for a modest-sized apartment building. The letter you receive at the beginning of the game notifying you of such also informs you that you’ve been given an experimental drug that will entirely suppress your need to sleep so as to allow you to more completely fulfill your duty to the state.

On the way into the building, you and your family run into the police rather brutally escorting the old landlord out. You’re told that he failed to complete his duties as a landlord, and now he’s facing the consequences– consequences that you will be subject to as well should you similarly fail.

From here, much of the way the plot plays out is up to you. Your task is to spy on your tenants and report them to the state. Personal details are encouraged in the reports, but more importantly, if you find anything that’s illegal or prohibited you must report it to the government at once.

There’s a brief mission at the beginning where you’re guided through the process of reporting on a particular tenant that ends in him being rather brutally evicted from the building by the police. The police arrive, burst through his door, search his apartment, and beat him before dragging him away, never to be seen again.

You’re given complete agency over Carl at this point, but your next mission from the government branch you report to (referred throughout the game as “The Ministry”) is to spy on another one of your tenants. To best do this, you have to talk to everyone else in the building, and as soon as you do that, things start to get messy.

Turns out the people in your building have personalities, and families, and motivations all their own. Some of them are devious, others are just kind people trying to get by, and most are somewhere between the two. And the tenant you’re supposed to spy on and his family are actually really nice people.

From that point on you’re at the mercy of many competing desires. Your family members all have needs and desires and bills to pay that you have to take care of, and none of it comes cheap. Your building tenants usually have their own problems that you may or may not want to help them with, and all the while you have to remember your state-mandated goals: report everything.

Gameplay

The gameplay in Beholder is a mixture of point and click adventure and time and resource management. It quickly becomes apparent that your main way of surviving throughout the game is to gather information on everything and everyone in your building. Regardless of who you decide your loyalties lie with, the only power you have is in the currency you have available, and you gain all of that currency by trading information about people. As a result, everything you do needs to be in pursuit of that knowledge.

There are several different ways you can go about this, and some are more insidious than others. Right off the bat, your boss tells you that one of the best ways to figure out what’s going on in your building is to install cameras everywhere. And he means everywhere. You install them in the common areas at first, but he also recommends you put them in the fire alarms in your tenants’ apartments.

In addition to that, you can peek in through the keyhole of apartments to see what the occupants are up to, or if you know they’re not at home you can simply walk in. You have all the keys, after all. Once you’re inside you can search everything or install cameras and then make notes on anything suspicious or otherwise interesting. Searching takes quite some time as every object takes a few seconds to begin searching and then you have to click through every object in the inventory to see if it’s anything useful or pertinent. A razor blade might mean nothing in an old woman’s apartment, but would be a red flag the Ministry is interested in if the tenant is a known dissident.

This mechanic means you need to keep a close eye on your tenant’s whereabouts at all times, which is augmented nicely by the game’s entire aesthetic. Characters look unique, and they pop against the background because of the way they’re colored so it’s never too difficult to see where they are in the building.

This turns out to be surprisingly fun, though it does sometimes come off as a little bit strange. You can search almost everything in an apartment, including television sets, telephones, end tables, and beds, but the objects in each thing you can search appear to be randomly generated. This leads to some dissonance with what you’re finding. It seems a bit unusual that someone would store a razor, books, a comb, and some bottles in their TV, or a toothbrush, metal parts, a coffee pot, glasses, and a watch on a single chair.

It never takes away from the fun, but it does subtract from the immersion. That’s unfortunate because in a game like this, immersion is critical. If you start to feel like you’re just ‘playing a game’ you’re not going to care about the tenants. You’re just going to try to ‘win’ with no regard for the characters that get hurt.

The only other major thing you’re going to want to do in someone’s apartment is steal, which brings me to the resource management side of the game.

This is where Beholder struggles the most. There are two major resources you’re dealing with: Reputation and Cash. Reputation can be used to ‘buy’ cameras from the Ministry to help you spy, but it can also be used to get others in the building to do favors for you, or force them to do something you want. You can earn reputation by submitting reports to the ministry or doing favors for people in the building.

The fact that this reputation is shared between the Ministry and your tenants is confusing at first, and not something I realized right away. In the beginning of the game, your boss explains that you can use reputation to buy cameras and mentions that it’s your ‘standing with the people’ and can be used to influence them. While this line of dialogue is accurate, I interpreted it incorrectly as I believe many would– I assumed the people I would be influencing were my fellow Ministry peers and not my tenants. Because I could buy cameras with reputation points, I assumed that it was my reputation with the government, but in fact this is a pooled resource and is your ‘general’ reputation with everyone.

As such, you can use reputation to help or hinder your tenants or use that same resource to buy the tools needed to spy on them– this makes little sense. Your reputation with the Ministry would not be the same as your reputation with the people living under the Ministry’s iron-fisted rule since the two essentially live at odds with one another.

If you’re helping a tenant, it’s usually because you’re subverting the ministry and vice versa. And since many of the instances you would ‘spend’ reputation with your tenants is to get them to do something they don’t want to do, it would make sense that you’re, in essence, trading some of the good will that you’d built up with them in exchange. But instead, you can spend the reputation you’ve earned by spying on them and reporting them to also get them to do things they don’t want to do. This lead me to getting almost half way through the game thinking that my reputation with my tenants was being tracked invisibly, and I didn’t know how much I had to spend at any given time.

I should mention that the only reason I got so far into the game without realizing this is because I decided to play as the perfect employee for my first game and report everyone and everything to the Ministry. This meant that I rarely, if ever, had need to cash in any favors with tenants– they weren’t generally in the building long enough for it to matter. Ultimately, while I feel the system could’ve been communicated better or the resource called something else, I can’t pin this all on the game, so take it with a grain of salt.

Because reputation is a shared resource, it’s nearly impossible to do even half of what you intend to do. On my first playthrough I spent every bit of reputation I got on cameras to spy on my tenants, but even then I wasn’t able to outfit the whole building by the end of the game, and I never had enough to cash in with anyone.

The same is true for cash. It’s very limited, and you’re constantly getting hit by expenses: Whether it’s paying the bills, buying a gift for your wife, getting some alcohol in exchange for a favor from a resident, or simply repairing an apartment in preparation for someone new to move in. The ways you can lose cash and reputation are numerous, but the ways both resources come in are very limited.

For both resources, the ‘cleanest’ way to earn them is from reporting on your tenants’ interests and activities (As long as those interests and activities aren’t outright illegal.)

Once you’ve documented that a tenant likes, say: knitting, chess, and going to the theater, you can compile a report to the Ministry on these activities. These reports must be accurate, or else instead of receiving a bonus for reporting them, you get fined. Luckily, everything about your tenant and what you’ve found is recorded in your journal, so it’s just a matter of transposing that information accurately into your report.

This does mean, however, that you’re burning away precious time as you compile your reports. Most quests for people or the ministry are timed, and you only have a certain number of in-game hours to complete them before you’re either fined, arrested, or the tenant you’re trying to help gives up on you. The longer it takes you to compile an accurate report, the less time you have to address the needs of the various forces vying for your attention. But with cash being as limited as it is, mistakes aren’t something you can generally afford to make.

If you do happen to find something illegal in someone’s apartment, you can choose to blackmail them instead of reporting them to the ministry. This gives you a thousand dollars if they agree to pay, but you can’t do this forever; and it’s contingent on you finding something illegal or planting something there.

You’re probably unlikely to have something illegal to plant unless you get lucky though. As the game progresses, the government constantly adds items to the list of illegal goods. One day it might be jeans, the next it’s classic music, and so on. Once these items are declared contraband they become incredibly expensive to buy, usually ranging from $2000 to $5000. The cheapest is an apple that can be bought for $725, and planted, which would give you a profit of $275 if you successfully blackmailed a tenant for possessing it.

So far, so good right? Bills aren’t too bad, ranging from $400 – $750. Sometimes I had to repair things in the building, which costs $50 a pop. Sometimes I had to buy things for people, or trade in to get something for someone, but it was manageable if I prioritized.

My problem with this system comes with the fact that early on you’re given one particular quest with dire consequences if you fail it. The cost for completing the quest? $20,000.

Up until this quest, you’ll have done a bunch of quests that drain your money and your reputation depending on how you deal with them. There are ways to mitigate this; some of your tenants might be able to get items for you cheaper than they would be if you bought them from the store, or sometimes they can even help you out for free, so you might at this point have under a thousand dollars or even up to $3500 depending on how aggressive you’ve been about reporting people, finding alternative solutions to quests that cost you less, blackmailing people with contraband, or stealing items from apartments and selling them for your own personal profit.

But despite restarting the game three or four times to get to this point (it’s very early on, so it’s easy to get to) and trying to delay the quest as much as possible, I was never able to get anywhere near the amount of money to finish the quest or find an alternate solution for it. As far as I can tell, it’s actually impossible to complete. The methods above are the only ways to make money that I’m aware of, and although the game tells you that you make money from renting the apartments, you don’t ever receive any. This wasn’t the only quest that was nearly impossible to complete either.

I don’t mind systems that force you into hard choices. If I have to sell out all of my tenants to the government so that I can take care of my family, no problem. That’s a tough choice when you know your innocent tenants are being thrown in prison because you blackmailed them or sold them out for a richer tenant, but if I do all that and I’m not even close to the asking sum, it makes it feel like the quest is designed to fail– and that’s not fun. Pretty soon it feels like it doesn’t really matter what you do, because you’re completely on rails either way.

There very well may be another way to raise the money or get around the cash requirements of these quests, as Beholder has many systems that are moving all at once, and the timing of quests can vary greatly depending on who you’ve chosen to rent an apartment out to and what you have or haven’t done for them, but if there was another way it wasn’t at all clear that it was an option.

It’s a shame, because Beholder very often succeeds in exactly that respect, always allowing you to raise the funds or reputation for something, but forcing you to sacrifice something else in order to do it, which is why these few major quests with such enormous requirements are so baffling. They’re an unfortunate pitfall of an otherwise interesting and compelling experience, and a rather large pock mark in an otherwise balanced-feeling resource system.

Overall

I really liked Beholder, and I had a lot of fun with it. It surpassed my expectations in almost every way, and despite a few balance issues, I think it’s worth its asking price.

The visuals and audio are excellent, the story is compelling, and most of the decisions you’re presented with make you hesitate, which is often difficult to achieve in games such as these.

In total it took me around 6 hours to complete, but there were a lot of things I could’ve done differently. I suspect I’ll be starting another game shortly to see if I can better manage my building or what happens if I decide to join the revolution instead of dutifully reporting everything to the Ministry. With multiple endings and usually at least two different ways to resolve each quest, there’s plenty of replay value to be had.

All in all, Beholder is an excellent first game from Warm Lamp Games, and if you’re into the theme or enjoy resource management games at all, Beholder is a no-brainer.

Pros

+ Great graphic style that allows characters to pop

+ Gets you to care about your tenants

+ Each quest has several solutions, offering replay value

Cons

– Randomized item placement breaks immersion

– Some quests feel nearly impossible to complete

– Reputation system could use some clarification early on

Add comment